By YOVANNA GARCIA

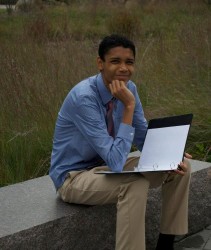

When first-generation student and Honduran immigrant Jonathan Fuentes entered college in 2012, he learned that he was academically unprepared to succeed in higher education. Despite being admitted to a selective school with an acceptance rate of 55.3 percent, he found himself struggling more than his peers, financially and academically.

“At some point I just wanted to quit high school and just start a job,” said Fuentes. “I can see why many people would prefer to just start working after high school rather than go to college—you start comparing yourself to the people around you, so it can be really difficult.

“In my classes, I see students around me doing things that I can’t really afford to do. It’s difficult because I feel stuck and it’s really hard to find a job on campus and even off campus. Mostly I’ve felt overwhelmed and powerless.”

Fuentes, a junior psychology student at Ramapo College, came to America as a 15-year-old searching for better opportunities in education and employment. Neither of his parents attended college nor speak English. Upon his arrival in America, he was placed in bilingual classes, but within a year he was able to learn more of the language and was transferred into mainstream courses with the rest of his peers. As a “decent student,” Fuentes was able to achieve passing grades in all of his high school courses.

Fuentes currently lives with his aunt in West New York, an impoverished town in Hudson County, N.J. He finds it to be “a little uncomfortable,” but cannot financially afford to return to Honduras right now.

Still, acclimating to American culture has not been easy.

Fuentes is a Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and a high school National School Lunch Program recipient, both federally assisted meal programs for low-income people. He describes himself as socially secluded from his peers who have financial support from their families as a means to get through college.

Fuentes often relies on free food events on campus for his daily meals since he is currently unemployed and unable to find a job.

The odds that a young person in the U.S. will be in higher education if his or her parents do not have upper secondary education are just 29 percent, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

And as our nation continues to lag in educational mobility due to growing disparities in wealth and income inequality, the American Dream has begun to move out of America. A dream that once served as a landscape to rise out of poverty, gain economic mobility and move a family forward is sounding less plausible, especially for immigrants and first-generation Americans.

For Fuentes, the idea of the American Dream is just that—a dream— since it only exists when you sleep and is unattainable for so many people.

“My idea of the American Dream is there really isn’t an American Dream for many people,” he said. “I want to be a guidance counselor or a counselor in general in order to give back to people who are in the position that I once was in in terms of emotional issues and mental health, but right now, honestly, I don’t think I can afford grad school. I just want to work [in the United States] and then go back to Honduras.”

It has been proven that people of color face greater barriers than their white counterparts in a country with a dark history of race-based discrimination and social inequality; and this social imbalance is further perpetuated by the lack of equal access to education among African-American and Latino communities.

The United States ranks 14th in the world in the percentage of 25-34 year-olds with higher education; and even then, the number of non-white people with college degrees is skewed.

In 2012, a study by the Pew Research Center found that Hispanics accounted for just 9 percent of young adults (ages 25 to 29) with bachelor’s degrees. This gap is driven, in part, by the fact that Hispanics are less likely than whites to enroll in a four-year college, attend a selective college and enroll full-time. The same study found that in 2012, blacks made up 14 percent of college-aged students (ages 18 to 24), yet just 9 percent of bachelor’s degrees earned by young adults.

With fewer enrichment programs available in poor schools and minority students almost always under-represented in the classes that are available, access-based programs are on the rise nationwide.

EOF as a nationwide support system

Fuentes is currently enrolled in the Educational Opportunity Fund (EOF) Program at Ramapo College, a nationwide initiative that provides support and access to higher education to students who exhibit the potential for success, but who come from financially disadvantaged families or communities.

The EOF Program provides eligible students with the support needed to maintain their continued enrollment through graduation by pairing the students with academic advisors who sometimes also serve as mentors.

[AUDIO: Listen to Marita Esposito talk about her mentorship role within the EOF program.]

“For those students who are with us from the beginning, we start with an intensive summer program to give them the toolkits necessary to address any kind of deficiency that may be there in order to succeed once they begin their careers at Ramapo,” said Marita Esposito, coordinator of leadership education in student activities for the EOF program. “From that point forward, we track students, not only in academic progress but also with their educational and career goals.”

EOF-eligible students like Fuentes receive grants and scholarships that minimize the financial burden of college attendance and services designed to foster academic success.

“Our fundamental mission has been to provide access to a four-year college from students who may come from underrepresented backgrounds and/or financial situations,” said Dee Foreman, the acting director of the Education Opportunity Fund Program. “There are school districts throughout the state of New Jersey that are underfunded in comparison to other schools located within upper class or middle class suburban towns.”

Foreman explained that as a result of underfunded school districts that may have a lack of books, disproportionate teacher-student ratios or classes too large for student learning, students from low-income districts are inadequately prepared for college. These factors set back students from these backgrounds when compared to their peers.

[AUDIO: Listen to Dee Foreman talk about the history of the EOF program.]

“The environment and financial factors are relative to a student’s ability to learn,” she adds.

Statewide EOF programs were established in 1967 as a result of riots that took place in Newark, N.J. that left the city and schools depleted socioeconomically and economically, but the program only first started at Ramapo in 1978.

The EOF class average has been between 95 and 105 students in the past few years, with the highest being at 116 just last summer. Foreman estimated that the retention is at about 99 percent following the EOF summer program; about 92 percent after the first year; and in the 80 percentile overall.

EOF students generally graduate between 5 and 6 years, but when they do graduate, the retention is actually higher than the generally admitted students that are at the college. However, many of the students who come into the EOF summer program together do not graduate together since many of the students may take semesters off to work or may not take 16 credits per semester.

To help students pay for college, the EOF program offers students opportunities for employment within its office.

“A lot of our students also work for us in student leadership positions, office assistants, research with different departments on campus, and mentorship programs that we set up in conjunction with SSHS, CA, the business program, etcetera,” said Esposito.

Esposito adds that for those students who are proactive and take the initiative, the EOF program does additional one-on-one appointments to help students with post-graduation plans, graduate school, and employment.

The roots of poverty embedded in American culture

While the EOF program does a lot to combat the racial inequality that is embedded in the culture of our society, a lack of resources for students from urban communities continues to stall social and economic mobility for poor people of color who are already historically disenfranchised.

A statistic published in a Children’s Defense Fund report states that the most dangerous place for a child to grow up in America is at the intersection of poverty and race. This study touches on an issue that is nationally affecting our population by producing social inequality in terms of pay gaps and access to education or employment opportunities.

Earlier in the month, The New York Times reported that children who grow up in certain places go on to earn much more than they would if they grew up elsewhere. Bergen County, for example, the county where Fuentes’s college is located, is very good for income mobility for children in poor families. It is better than about 88 percent of counties nationwide; whereas other, severely poor counties such as Camden and Passaic County are very bad for income mobility, according to the report. They are better than only about 18 and 7 percent of counties, respectively.

According to the 2009-2013 figures from the U.S. Census Bureau, the percent of persons below poverty level in the city of Passaic increased to 30.3 percent. Camden, the poorest city in the nation, had 39.8 percent of its residents living below the poverty line.

The state’s poorest county is Passaic, followed by Cumberland, Essex and Hudson, according to a report released in 2013.

More than fifty years after Brown v. Board of Education promised equal educational opportunities for all children, a growing crisis of separate and unequal education still affects the nation. Millions of students are still not getting the basic education they need to thrive in America.

New Jersey is the 5th most segregated state for African Americans and 4th most segregated state for Hispanics.

These numbers represent the systems of inequality that exist just in New Jersey, since the makeup of these cities is predominantly made up of people of color with little access to education and high paying jobs.

While it may seem that poverty only exists overseas or in third world countries, students like Fuentes have experienced this inequality firsthand.

“If my dad would’ve had a better job, if he’d had a higher education to be able to guide me or if I had a better background, I believe I would have done better in general,” said Fuentes. “It’s really interesting actually, even though I had less growing up, I was very happy. Then when I came to America, is when I started comparing my life to other people and I guess I started to conform and started to feel the social pressures affecting me, so I started wanting more things.”

Having come from a very poor working-class family in Honduras, Fuentes attributes becoming Buddhist to his newfound belief that less is more. Since he is unable to afford living in New Jersey—or the United States for that matter—he hopes to graduate with his Bachelor of Arts in Psychology from Ramapo and plans to buy a home in Honduras, where he can live as simply as possible.

“I’m trying to get back to who I really am,” he said. “I’m starting to realize that I don’t need many things — but without the education that I have now, I would have never been able to reach that conclusion.”